The phrase separation of church and state is NOT in our Constitution.

Today, many Americans think that the First Amendment says "Separation of Church and State". The Courts and the media will often refer to a ruling as being in violation of the Separation of Church and State. A recent national poll showed that 69% of Americans believe that the First Amendment says Separation of Church and State. You may be surprised to learn that these words do not appear in the First Amendment or anywhere else in the Constitution! Here is what the First Amendment actually does say.

The First Amendment:

"Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

So where did the words "Separation of Church and State" come from? They can be traced back to a letter that Thomas Jefferson wrote back in 1802. In October 1801, the Danbury Baptist Association of Connecticut wrote to President Jefferson, and in their letter they voiced some concerns about Religious Freedom. On January 1, 1802 Jefferson wrote a letter to them in which he added the phrase "Separation of Church and State." When you read the full letter, you will understand that Jefferson was simply underscoring the First Amendment as a guardian of the peoples religious freedom from government interference. Here is an excerpt from Jefferson's letter.

"I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, prohibiting the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and State."

If actions speak stronger than words, it is interesting to note that 3 days after Jefferson wrote those words, he attended church in the largest congregation in North America at the time. This church held its weekly worship services on government property, in the House Chambers of the U.S. Capital Building. The wall of separation applies everywhere in the country even on government property, without government interference. This is how it is written in the Constitution, this is how Thomas Jefferson understood it from his letter and actions, and this is how the men who wrote the Constitution practiced it.

By the way, do you know what constitution DOES have the phrase "separation of church and state"? Why yes, the Soviet Union has this phrase in their constitution.

The 1936 U.S.S.R. Constitution

"ARTICLE 124. In order to ensure to citizens freedom of conscience, the church in the U.S.S.R. is separated from the state, and the school from the church. Freedom of religious worship and freedom of antireligious propaganda is recognized for all citizens."

The 1977 U.S.S.R. Constitution

"Article 52. Citizens of the USSR are guaranteed freedom of conscience, that is, the right to profess or not to profess any religion, and to conduct religious worship or atheistic propaganda. Incitement of hostility or hatred on religious grounds is prohibited. In the USSR, the church is separated from the state, and the school from the church."

Thanks to schoolprayerinamerica where I found this info

Keith Olbermann & Rob Boston discuss Glenn Beck and Separation of Church And State. From Countdown, MSNBC.

[download]

Now I want you to listen to some of the things they say in this discussion. They're talking about David Barton from wallbuilders.com and discuss how he wrote a book and made up "fake quotes" from the founders and they were "completely fabricated" and that the people from the right "invent new history" to backup their arguments. They also say that the book from David Barton was re-written and re-named because of the mis-information. Note that the guy talking to Keith Olbermann is from a group called "Americans United For Separation Of Church And State". Notice though that they never say that his second book had any mis-quotes(more on that later).

Now I have to point out something here. The book that they're dumping on from David Barton was written TEN YEARS AGO! And I have to now show you an article that David Barton wrote in January, 2000.

Raising The Academic Standard For Quoting The Founding Fathers

In 1988, David Barton published The Myth of Separation, documenting the Founding Fathers religious beliefs and practices with over 700 footnotes. In that work, he cited from several sources, including history professors, legal scholars, and early textbooks. Although this is common practice in the academic community, David came to believe that historical debates undergirding public policy should be conducted using a standard of evidence that would be accepted by courts: only the "best evidence" should be used (e.g., eyewitness testimony, direct statements and actions by the participants, etc.). In other words, instead of quoting what a professor or judge said about Thomas Jefferson's (or the other 200+ Founding Fathers') views on the First Amendment, let Jefferson's (and the other Founders') own words and actions speak for themselves.

Consequently, David authored a second book (Original Intent, with over 1,400 footnotes) on the same theme as The Myth of Separation in which he does not use Founder's quotes unless they are documented to a primary source; he dropped all "historical" quotes from attorneys, professors, texts, etc.

In using this higher standard, he discovered there were about a dozen or so popular and widely-used quotes by historians and others (David had quoted these sources with documentation properly footnoted in The Myth of Separation) that he could not find in the Founders' own writings. Importantly, some of those quotes had come from works nearly a century-and-a-half old and therefore would seem to have been credible; yet David could not find those quotes in original documents.

David therefore released a paper entitled "Unconfirmed Quotations" in which he listed those dozen or so quotes that he had used in Myth of Separation and which he would voluntarily no longer use. He called on those on all sides of the debate to refrain from using these quotes in any subsequent writings until their veracity could be established in a source that would meet the legal standard of "best evidence." (Since the release of that article, we have actually been able to find the original documentation for some of those quotes that we originally listed as "unconfirmed" - and which antagonists claim that David had made up!)

Despite David's clear statement in the preface of "Unconfirmed Quotations" that he intended to raise the academic bar, David's antagonists (such as Rob Boston, et. al) claimed David had "admitted he made up his quotes" "" a complete mischaracterization of what occurred. On the contrary, David had simply challenged authors on all sides "" whether writing for the American Atheist Association or the National Association of Evangelicals, for Americans United for Separation of Church and State or for Christian Coalition - that they should not allege that the Founders said or believed something unless it could be documented in the Founders' own writings or some other equally authoritative source (e.g., the Records of the Continental Congress, Madison's notes on the Constitutional Convention, the Debates of the First Congress, etc.).

It is significant that David's critics point to The Myth of Separation when they claim he "admits that he made up his quotes" but they remain completely silent about Original Intent. Both works arrive at exactly the same historical conclusion, but the history is "made up" in the one but not the other? To date, none of David's antagonists have ever been able to point out a single example in Original Intent in which he "made up a quote." They cannot do so. For that matter, they could not do so in The Myth of Separation either. Rather, they just continue to claim he "admits that he makes up his quotes."

The mischaracterizations of what David did were so egregiously untrue that distinguished attorneys who practice law before the U. S. Supreme Court asked David if they could sue these groups and individuals for libel and slander. Despite the difficult free-speech standards that courts have established to prove libel and slander, the attorneys still believed that they would prevail. To date, David has declined to proceed on the legal front, although such a suit remains a definite possibility. (By the way, some members and supporters of the organizations criticizing David actually resigned in protest over the mischaracterizations made about him by their own organizations; while they did not share David's philosophical viewpoint, they were offended by the blatant misportrayals their own organizations had made about David's work in a scurrilous effort to discredit him.) In short, there is no factual basis behind this charge, nor has any antagonist ever successfully pointed out even one occasion in which David fabricated any quote. David's work stands on its own merits for those who wish to verify his documentation rather than simply accepting mischaracterizations of his work without personal investigation.

Now, please watch this video from the Glenn Beck Show on our founding.

[download]

Then there's this from Rachel Maddow From August 10, 2010

[download]

Religious Oaths and Tests

In addition, many states required tests to keep non-Christians or in some cases Catholics out of public office:

- The New Jersey Constitution of 1776 restricted public office to all but Protestants by its religious test/oath.

- The Delaware Constitution of 1776 demanded an acceptance of the Trinity by its religious test/oath.

- The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 had a similar test/oath.

- The Maryland Constitution of 1776 had such a test/oath.

- The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 had a test/oath that restricted all but Protestants from public office.

- The Georgia Constitution of 1777 used an oath/test to screen out all but Protestants.

- The Vermont state charter/constitution of 1777 echoed the Pennsylvania Constitution regarding a test/oath.

- The South Carolina Constitution of 1778 had such a test/oath allowing only Protestants to hold office.

- The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 and New Hampshire Constitution of 1784 restricted such office holders to Protestants.

- Only Virginia and New York did not have such religious tests/oaths during this time period.

XIX. That there shall be no establishment of any one religious sect in this Province, in preference to another; and that no Protestant inhabitant of this Colony shall be denied the enjoyment of any civil right, merely on account of his religious principles; but that all persons, professing a belief in the faith of any Protestant sect. who shall demean themselves peaceably under the government, as hereby established, shall be capable of being elected into any office of profit or trust, or being a member of either branch of the Legislature, and shall fully and freely enjoy every privilege and immunity, enjoyed by others their fellow subjects.

ART. 22. Every person who shall be chosen a member of either house, or appointed to any office or place of trust, before taking his seat, or entering upon the execution of his office, shall take the following oath, or affirmation, if conscientiously scrupulous of taking an oath, to wit:

" I, A B. will bear true allegiance to the Delaware State, submit to its constitution and laws, and do no act wittingly whereby the freedom thereof may be prejudiced."

And also make and subscribe the following declaration, to wit:

" I, A B. do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed for evermore; and I do acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration."

And all officers shall also take an oath of office.

SECT. 10. A quorum of the house of representatives shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of members elected; and having met and chosen their speaker, shall each of them before they proceed to business take and subscribe, as well the oath or affirmation of fidelity and allegiance hereinafter directed, as the following oath or affirmation, viz:

I do swear (or affirm) that as a member of this assembly, I will not propose or assent to any bill, vote, or resolution, which stall appear to free injurious to the people; nor do or consent to any act or thing whatever, that shall have a tendency to lessen or abridge their rights and privileges, as declared in the constitution of this state; but will in all things conduct myself as a faithful honest representative and guardian of the people, according to the best of only judgment and abilities.

And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz:

I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration.

And no further or other religious test shall ever hereafter be required of any civil officer or magistrate in this State.

LV. That every person, appointed to any office of profit or trust, shall, before he enters on the execution thereof, take the following oath; to wit :–"I, A. B., do swear, that I do not hold myself bound in allegiance to the King of Great Britain, and that I will be faithful, and bear true allegiance to the State of Maryland;" and shall also subscribe a declaration of his belief in the Christian religion.

32. That no person who shall deny the being of God, or the truth of the Protestant religion, or the divine authority of either the Old or New Testaments, or who shall hold religious principles incompatible with the freedom and safety of the State, shall b e capable of holding any office, or place of trust or profit, in the civil department, within this State.

ART. VI. The representatives shall be chosen out of the residents in each county, who shall have resided at least twelve months in this State, and three months in the county where they shall be elected; except the freeholders of the counties of Glynn and Camden, who are in a state of alarm, and who shall have the liberty of choosing one member each, as specified in the articles of this constitution, in any other county, until they have residents sufficient to qualify them for more; and they shall be of the Protestent religion, and of the age of twenty-one years, and shall be possessed in their own right of two hundred and fifty acres of land, or some property to the amount of two hundred and fifty pounds.

SECTION IX. A quorum of the house of representatives shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of members elected; and having met and chosen their speaker, shall, each of them, before they proceed to business, take and subscribe, as well the oath of fidelity and allegiance herein after directed, as the following oath or affirmation, viz.

" I ____ do solemnly swear, by the ever living God, (or, I do solemnly affirm in the presence of Almighty God) that as a member of this assembly, I will not propose or assent to any bill, vote, or resolution, which shall appear to me injurious to the people; nor do or consent to any act or thing whatever, that shall have a tendency to lessen or abridge their rights and privileges, as declared in the Constitution of this State; but will, in all things' conduct myself as a faithful, honest representative and guardian of the people, according to the best of my judgment and abilities."

And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz.

" I ____ do believe in one God, the Creator and Governor of the Diverse, the rewarder of the good and punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the scriptures of the old and new testament to be given by divine inspiration, and own and profess the protestant religion."

And no further or other religious test shall ever, hereafter, be required of any civil officer or magistrate in this State.

III. That as soon as may be after the first meeting of the senate and house of representatives, and at every first meeting of the senate and house of representatives thereafter, to be elected by virtue of this constitution, they shall jointly in the house of representatives choose by ballot from among themselves or from the people at large a governor and commander-in-chief, a lieutenant-governor, both to continue for two years, and a privy council, all of the Protestant religion, and till such choice shall be made the former president or governor and commander-in-chief, and vice-president or lieutenant-governor, as the case may be, and privy council, shall continue to act as such.

Massachusetts Art. III. As the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depend upon piety, religion, and morality, and as these cannot be generally diffused through a community but by the institution of the public worship of God and of the public instructions in piety, religion, and morality: Therefore, To promote their happiness and to secure the good order and preservation of their government, the people of this commonwealth have a right to invest their legislature with power to authorize and require, and the legislature shall, from time to time, authorize and require, the several towns, parishes, precincts, and other bodies-politic or religious societies to make suitable provision, at their own expense, for the institution of the public worship of God and for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety, religion, and morality in all cases where such provision shall not be made voluntarily.

And the people of this commonwealth have also a right to, and do, invest their legislature with authority to enjoin upon all the subject an attendance upon the instructions of the public teachers aforesaid, at stated times and seasons, if there be any on whose instructions they can conscientiously and conveniently attend.

Provided, notwithstanding, That the several towns, parishes, precincts, and other bodies-politic, or religious societies, shall at all times have the exclusive right and electing their public teachers and of contracting with them for their support and maintenance.

And all moneys paid by the subject to the support of public worship and of public teachers aforesaid shall, if he require it, be uniformly applied to the support of the public teacher or teachers of his own religious sect or denomination, provided there be any on whose instructions he attends; otherwise it may be paid toward the support of the teacher or teachers of the parish or precinct in which the said moneys are raised.

And every denomination of Christians, demeaning themselves peaceably and as good subjects of the commonwealth, shall be equally under the protection of the law; and no subordination of any sect or denomination to another shall ever be established by law.

New Hampshire VI. As morality and piety, rightly grounded on evangelical principles, will give the best and greatest security to government, and will lay in the hearts of men the strongest obligations to due subjection; and as the knowledge of these, is most likely to be propagated through a society by the institution of the public worship of the DEITY, and of public instruction in morality and religion; therefore, to promote those important purposes, the people of this state have a right to impower, and do hereby fully impower the legislature to authorize from time to time, the several towns, parishes, bodies corporate, or religious societies within this state, to make adequate provision at their own expence, for the support and maintenance of public protestant teachers of piety, religion and morality:

Provided notwithstanding, That the several towns, parishes, bodies-corporate, or religious societies, shall at all times have the exclusive right of electing their own public teachers, and of contracting with them for their support and maintenance. And no portion of any one particular religious sect or denomination, shall ever be compelled to pay towards the support of the teacher or teachers of another persuasion, sect or denomination.

And every denomination of christians demeaning themselves quietly, and as good subjects of the state, shall be equally under the protection of the law: and no subordination of any one sect or denomination to another, shall ever be established by law.

And nothing herein shall be understood to affect any former contracts made for the support of the ministry; but all such contracts shall remain, and be in the same state as if this constitution had not been made.

Virginia Constitution of 1776

SEC. 16. That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.

Religion in the Original 13 Colonies

Aitken Bible

09/12/1782

Prior to the American Revolution, the only English Bibles in the colonies were imported either from Europe or England. Publication of the Bible was regulated by the British government, and required a special license. Robert Aitken's Bible was the first known English-language Bible to be printed in America, and also the only Bible to receive Congressional approval. Aitken's Bible, sometimes referred to as "The Bible of the Revolution," is one of the rarest books in the world, with few copies still in existence today.

|

History of the Aitken Bible

On January 21, 1781, Robert Aitken presented a "memorial" [petition] to Congress offering to print "a neat Edition of the Holy Scriptures for the use of schools." This is the text of that memorial:

To the Honourable The Congress

of the United States of America

The Memorial of Robert Aitken

of the City of Philadelphia, Printer

Humbly Sheweth

That in every well regulated Government in Christendom The Sacred Books of the Old and New Testament, commonly called the Holy Bible, are printed and published under the Authority of the Sovereign Powers, in order to prevent the fatal confusion that would arise, and the alarming Injuries the Christian Faith might suffer from the Spurious and erroneous Editions of Divine Revelation. That your Memorialist has no doubt but this work is an Object worthy the attention of the Congress of the United States of America, who will not neglect spiritual security, while they are virtuously contending for temporal blessings. Under this persuasion your Memorialist begs leave to, inform your Honours That he both begun and made considerable progress in a neat Edition of the Holy Scriptures for the use of schools, But being cautious of suffering his copy of the Bible to Issue forth without the sanction of Congress, Humbly prays that your Honours would take this important matter into serious consideration & would be pleased to appoint one Member or Members of your Honourable Body to inspect his work so that the same may be published under the Authority of Congress. And further, your Memorialist prays, that he may be commissioned or otherwise appointed & Authorized to print and vend Editions of, the Sacred Scriptures, in such manner and form as may best suit the wants and demands of the good people of these States, provided the same be in all things perfectly consonant to the Scriptures as heretofore Established and received amongst us.

After appointing a committee to study the project, Congress acted on September 12, 1782, by "highly approv[ing of] the pious and laudable undertaking of Mr. Aitken." The endorsement by Congress was printed in the Aitken Bible:

|

The endorsement was signed by Charles Thomson, who was Secretary of the Continental Congress. Thomson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, is also famous for "Thomson's Bible," the first American translation of the Greek Septuagint, published in 1808 (Thomson was an accomplished theologian, publishing such works as "A Regular History of the Conception, Birth, Doctrine, Miracles, Death, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus Christ.")

Robert Aitken printed three documents in the front of his Bible, the report of the committee established to review his memorial; the report of the Congressional Chaplains; and Congresses endorsement. Below is the text of these documents:

BY THE UNITED STATES IN CONGRESS ASSEMBLED:

September 12th, 1782.

THE Committee to whom was referred a Memorial of Robert Aitken, printer, dated 21st January, 1781, respecting an edition of the Holy Scriptures, report, "That Mr. Aitken has, at a great expense, now finished an American edition of the Holy Scriptures in English; that the Committee have from time to time attended to his progress in the work; that they also recommended it to the two Chaplains of Congress to examine and give their opinion of the execution, who have accordingly reported thereon; the recommendation and report being as follows:

"Philadelphia, 1st September, 1782.

"Reverend Gentlemen,

"Our knowledge of our piety and public spirit leads us without apology to recommend to your particular attention the edition of the Holy Scriptures publishing by Mr. Aitken. He undertook this expensive work at a time when, from the circumstances of the war, and English edition of the Bible could not be imported, nor any opinion formed how long the obstruction might continue. On this account particularly he deserves applause and encouragement. We therefore wish you, Reverend Gentlemen, to examine the execution of the work, and if approved, to give the sanction of our judgment, and the weigh of your recommendation.

We are, with very great respect,

Your most obedient humble servants.

(Sign'd) JAMES DUANE, Chairman in behalf

of a Committee of Congress on Mr. Atken's Memorial.

Reverend Doct. White and Revd. Mr. Duffield,

Chaplains of the United States in Congress assembled.

Report.

Gentlemen,

AGREEABLY to your desire we have paid attention to Mr. Robert Aitken's impression of the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament. Having selected and examined a variety of passages throughout the work, we are of opinion that it is executed with great accuracy as to the sense, and with as few grammatical and typographical errors as could be expected in an undertaking of such magnitude. Being ourselves witnesses of the demand for this invaluable book, we rejoice in the present prospect of a supply; hoping that it will prove as advantageous as it is honorable to the Gentleman, who has exerted himself to furnish it, at the evident risk of private fortune. We are, Gentlemen,

Your very respectful and humble servants,

(Sign'd) WILLIAM WHITE,

GEORGE DUFFIELD.

Philadelphia, September 10th, 1782.

Honble James Duane, Esq. Chairman, and the other

Honble Gentlemen of the Committee of Congress on

Mr. Aitken's Memorial."

Whereupon,

RESOLVED,

THAT the United States in Congress assembled highly approve the pious and laudable undertaking of Mr. Aitken, as subservient to the interest of religion, as well as an instance of the progress of arts in this country, and being satisfied from the above report of his care and accuracy in the execution of the work, they recommend this edition of the Bible to the inhabitants of the United States, and hereby authorize him to publish this Recommendation in the manner he shall think proper.

CHA. THOMSON, Sec'ry.

In 1968, the American Bible Society reprinted the Aitken Bible, this is the title page of that reprint:

|

IV. Religion and the Congress of the Confederation, 1774-89

The Continental-Confederation Congress, a legislative body that governed the United States from 1774 to 1789, contained an extraordinary number of deeply religious men. The amount of energy that Congress invested in encouraging the practice of religion in the new nation exceeded that expended by any subsequent American national government. Although the Articles of Confederation did not officially authorize Congress to concern itself with religion, the citizenry did not object to such activities. This lack of objection suggests that both the legislators and the public considered it appropriate for the national government to promote a nondenominational, nonpolemical Christianity.

Congress appointed chaplains for itself and the armed forces, sponsored the publication of a Bible, imposed Christian morality on the armed forces, and granted public lands to promote Christianity among the Indians. National days of thanksgiving and of "humiliation, fasting, and prayer" were proclaimed by Congress at least twice a year throughout the war. Congress was guided by "covenant theology," a Reformation doctrine especially dear to New England Puritans, which held that God bound himself in an agreement with a nation and its people. This agreement stipulated that they "should be prosperous or afflicted, according as their general Obedience or Disobedience thereto appears." Wars and revolutions were, accordingly, considered afflictions, as divine punishments for sin, from which a nation could rescue itself by repentance and reformation.

The first national government of the United States, was convinced that the "public prosperity" of a society depended on the vitality of its religion. Nothing less than a "spirit of universal reformation among all ranks and degrees of our citizens," Congress declared to the American people, would "make us a holy, that so we may be a happy people."

The Liberty Window The Liberty WindowAt its initial meeting in September 1774 Congress invited the Reverend Jacob Duché (1738-1798), rector of Christ Church, Philadelphia, to open its sessions with prayer. Duché ministered to Congress in an unofficial capacity until he was elected the body's first chaplain on July 9, 1776. He defected to the British the next year. Pictured here in the bottom stained-glass panel is the first prayer in Congress, delivered by Duché. The top part of this extraordinary stained glass window depicts the role of churchmen in compelling King John to sign the Magna Carta in 1215.

Stained glass and lead, from The Liberty Window, Christ Church, Philadelphia, after a painting by Harrison Tompkins Matteson, c. 1848 Courtesy of the Rector, Church Wardens and Vestrymen of Christ Church, Philadelphia (101)

Oil on canvas by Charles Peale Polk, 1790 Independence National Historical Park Collection, Philadelphia (103)

Broadside, April 22, 1782 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (102)

Holograph notes, Benjamin Franklin (left) and Thomas Jefferson (right) Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (104-105)

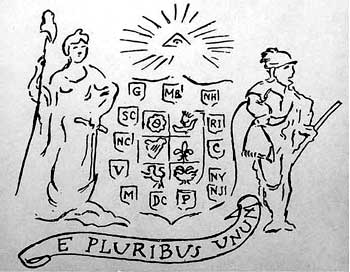

"Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God." Drawing by Benson Lossing, for Harper's New Monthly Magazine, July 1856. General Collections, Library of Congress. (106) First Great Seal Committee – July/August 1776

For the design team, Congress chose three of the five men who were on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Although these distinguished committee members were among the ablest minds in the new nation, they had little knowledge of heraldry. To help convey their vision, they chose the artist Pierre Eugène Du Simitière to work with them. Skilled in portraiture and heraldry (the state seals of Delaware and New Jersey are his designs), Du Simitière was also an avid collector of all things American and founded the first history museum in the United States. The four men consulted among themselves between July 4 and August 13, then each brought before the committee a suggestion for the design of the Great Seal. Benjamin Franklin's proposal is preserved in a note of his own handwriting: "Moses standing on the Shore, and extending his Hand over the Sea, thereby causing the same to overwhelm Pharaoh who is sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his Head and a Sword in his Hand. Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Clouds reaching to Moses, to express that he acts by Command of the Deity. Thomas Jefferson also suggested allegorical scenes. For the front of the seal: children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. For the reverse: Hengist and Horsa, the two brothers who were the legendary leaders of the first Anglo-Saxon settlers in Britain. John Adams chose the allegorical painting known as the "Judgment of Hercules" where the young Hercules must choose to travel either on the flowery path of self-indulgence or ascend the rugged, uphill way of duty to others and honor to himself. Du Simitière designed a proper heraldic seal that the committee liked and submitted to Congress on August 20, 1776: "The shield has six Quarters... pointing out the Countries from which these States have been peopled."

The shield is bordered with the initials for "each of the thirteen independent States of America."

Supporting the Shield on its right side: "The Goddess of Liberty in a corslet of armour alluding to the present Times, holding in her right hand the Spear & Cap and with her left supporting the Shield of the states."

Below left is an 1856 realization of the first committee's design. (The states' initials should be around the shield, not the outside of the seal.) On the right is the reverse side (also drawn in 1856).

The Reverse Side of the Great Seal "Pharaoh sitting in an open Chariot, a Crown on his head and a Sword in his hand, passing through the divided Waters of the Red Sea in Pursuit of the Israelites: Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Cloud, expressive of the divine Presence and Command, beaming on Moses who stands on the shore and extending his hand over the Sea causes it to overwhelm Pharaoh." Motto: "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God" The same day Congress received the committee's report, it was "Ordered, To lie on the table." In other words, Congress was unimpressed by their design.

Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (107)

Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (108)

Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (109)

Broadside Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (110)

and filling out Privateers, together with the Rules and Regulations of the Navy, and Instructions to Private Ships of War [page 16] - [page 17] Philadelphia: John Dunlap, 1776 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (113)

Horn, c. 1876 Mariner's Museum, Newport News, Virginia (114)

Philadelphia: David C. Claypoole, 1782 from the Journals of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (115)

Philadelphia: printed and sold by R. Aitken, 1782 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (116)

Broadside, Continental Congress, 1785 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (117)

Broadside, Continental Congress, 1787 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (118)

Records of the Continental Congress in the Constitutional Convention, July 27, 1787 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (119)

of the United Brethren [left page] - [right page] David Zeisberger Philadelphia: Mary Cist, 1806 Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (120)

|

The Separation of Church and State

David Barton - 01/2001

In 1947, in the case Everson v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court declared, "The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach." The "separation of church and state" phrase which they invoked, and which has today become so familiar, was taken from an exchange of letters between President Thomas Jefferson and the Baptist Association of Danbury, Connecticut, shortly after Jefferson became President.

The election of Jefferson – America's first Anti-Federalist President – elated many Baptists since that denomination, by-and-large, was also strongly Anti-Federalist. This political disposition of the Baptists was understandable, for from the early settlement of Rhode Island in the 1630s to the time of the federal Constitution in the 1780s, the Baptists had often found themselves suffering from the centralization of power.

Consequently, now having a President who not only had championed the rights of Baptists in Virginia but who also had advocated clear limits on the centralization of government powers, the Danbury Baptists wrote Jefferson a letter of praise on October 7, 1801, telling him:

Among the many millions in America and Europe who rejoice in your election to office, we embrace the first opportunity . . . to express our great satisfaction in your appointment to the Chief Magistracy in the United States. . . . [W]e have reason to believe that America's God has raised you up to fill the Chair of State out of that goodwill which He bears to the millions which you preside over. May God strengthen you for the arduous task which providence and the voice of the people have called you. . . . And may the Lord preserve you safe from every evil and bring you at last to his Heavenly Kingdom through Jesus Christ our Glorious Mediator. [1]

However, in that same letter of congratulations, the Baptists also expressed to Jefferson their grave concern over the entire concept of the First Amendment, including of its guarantee for "the free exercise of religion":

Our sentiments are uniformly on the side of religious liberty: that religion is at all times and places a matter between God and individuals, that no man ought to suffer in name, person, or effects on account of his religious opinions, [and] that the legitimate power of civil government extends no further than to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor. But sir, our constitution of government is not specific. . . . [T]herefore what religious privileges we enjoy (as a minor part of the State) we enjoy as favors granted, and not as inalienable rights. [2]

In short, the inclusion of protection for the "free exercise of religion" in the constitution suggested to the Danbury Baptists that the right of religious expression was government-given (thus alienable) rather than God-given (hence inalienable), and that therefore the government might someday attempt to regulate religious expression. This was a possibility to which they strenuously objected-unless, as they had explained, someone's religious practice caused him to "work ill to his neighbor."

Jefferson understood their concern; it was also his own. In fact, he made numerous declarations about the constitutional inability of the federal government to regulate, restrict, or interfere with religious expression. For example:

[N]o power over the freedom of religion . . . [is] delegated to the United States by the Constitution. Kentucky Resolution, 1798 [3]

In matters of religion, I have considered that its free exercise is placed by the Constitution independent of the powers of the general [federal] government. Second Inaugural Address, 1805 [4]

[O]ur excellent Constitution . . . has not placed our religious rights under the power of any public functionary. Letter to the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1808 [5]

I consider the government of the United States as interdicted [prohibited] by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions . . . or exercises. Letter to Samuel Millar, 1808 [6]

Jefferson believed that the government was to be powerless to interfere with religious expressions for a very simple reason: he had long witnessed the unhealthy tendency of government to encroach upon the free exercise of religion. As he explained to Noah Webster:

It had become an universal and almost uncontroverted position in the several States that the purposes of society do not require a surrender of all our rights to our ordinary governors . . . and which experience has nevertheless proved they [the government] will be constantly encroaching on if submitted to them; that there are also certain fences which experience has proved peculiarly efficacious [effective] against wrong and rarely obstructive of right, which yet the governing powers have ever shown a disposition to weaken and remove. Of the first kind, for instance, is freedom of religion. [7]

Thomas Jefferson had no intention of allowing the government to limit, restrict, regulate, or interfere with public religious practices. He believed, along with the other Founders, that the First Amendment had been enacted only to prevent the federal establishment of a national denomination – a fact he made clear in a letter to fellow-signer of the Declaration of Independence Benjamin Rush:

[T]he clause of the Constitution which, while it secured the freedom of the press, covered also the freedom of religion, had given to the clergy a very favorite hope of obtaining an establishment of a particular form of Christianity through the United States; and as every sect believes its own form the true one, every one perhaps hoped for his own, but especially the Episcopalians and Congregationalists. The returning good sense of our country threatens abortion to their hopes and they believe that any portion of power confided to me will be exerted in opposition to their schemes. And they believe rightly. [8]

Jefferson had committed himself as President to pursuing the purpose of the First Amendment: preventing the "establishment of a particular form of Christianity" by the Episcopalians, Congregationalists, or any other denomination.

Since this was Jefferson's view concerning religious expression, in his short and polite reply to the Danbury Baptists on January 1, 1802, he assured them that they need not fear; that the free exercise of religion would never be interfered with by the federal government. As he explained:

Gentlemen, – The affectionate sentiments of esteem and approbation which you are so good as to express towards me on behalf of the Danbury Baptist Association give me the highest satisfaction. . . . Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God; that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship; that the legislative powers of government reach actions only and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall of separation between Church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties. I reciprocate your kind prayers for the protection and blessing of the common Father and Creator of man, and tender you for yourselves and your religious association assurances of my high respect and esteem. [9]

Jefferson's reference to "natural rights" invoked an important legal phrase which was part of the rhetoric of that day and which reaffirmed his belief that religious liberties were inalienable rights. While the phrase "natural rights" communicated much to people then, to most citizens today those words mean little.

By definition, "natural rights" included "that which the Books of the Law and the Gospel do contain." [10] That is, "natural rights" incorporated what God Himself had guaranteed to man in the Scriptures. Thus, when Jefferson assured the Baptists that by following their "natural rights" they would violate no social duty, he was affirming to them that the free exercise of religion was their inalienable God-given right and therefore was protected from federal regulation or interference.

So clearly did Jefferson understand the Source of America's inalienable rights that he even doubted whether America could survive if we ever lost that knowledge. He queried:

And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure if we have lost the only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with His wrath? [11]

Jefferson believed that God, not government, was the Author and Source of our rights and that the government, therefore, was to be prevented from interference with those rights. Very simply, the "fence" of the Webster letter and the "wall" of the Danbury letter were not to limit religious activities in public; rather they were to limit the power of the government to prohibit or interfere with those expressions.

Earlier courts long understood Jefferson's intent. In fact, when Jefferson's letter was invoked by the Supreme Court (only twice prior to the 1947 Everson case – the Reynolds v. United States case in 1878), unlike today's Courts which publish only his eight-word separation phrase, that earlier Court published Jefferson's entire letter and then concluded:

Coming as this does from an acknowledged leader of the advocates of the measure, it [Jefferson's letter] may be accepted almost as an authoritative declaration of the scope and effect of the Amendment thus secured. Congress was deprived of all legislative power over mere [religious] opinion, but was left free to reach actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order. (emphasis added) [12]

That Court then succinctly summarized Jefferson's intent for "separation of church and state":

[T]he rightful purposes of civil government are for its officers to interfere when principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order. In th[is] . . . is found the true distinction between what properly belongs to the church and what to the State. [13]

With this even the Baptists had agreed; for while wanting to see the government prohibited from interfering with or limiting religious activities, they also had declared it a legitimate function of government "to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor."

That Court, therefore, and others (for example, Commonwealth v. Nesbit and Lindenmuller v. The People), identified actions into which – if perpetrated in the name of religion – the government did have legitimate reason to intrude. Those activities included human sacrifice, polygamy, bigamy, concubinage, incest, infanticide, parricide, advocation and promotion of immorality, etc.

Such acts, even if perpetrated in the name of religion, would be stopped by the government since, as the Court had explained, they were "subversive of good order" and were "overt acts against peace." However, the government was never to interfere with traditional religious practices outlined in "the Books of the Law and the Gospel" – whether public prayer, the use of the Scriptures, public acknowledgements of God, etc.

Therefore, if Jefferson's letter is to be used today, let its context be clearly given – as in previous years. Furthermore, earlier Courts had always viewed Jefferson's Danbury letter for just what it was: a personal, private letter to a specific group. There is probably no other instance in America's history where words spoken by a single individual in a private letter – words clearly divorced from their context – have become the sole authorization for a national policy. Finally, Jefferson's Danbury letter should never be invoked as a stand-alone document. A proper analysis of Jefferson's views must include his numerous other statements on the First Amendment.

For example, in addition to his other statements previously noted, Jefferson also declared that the "power to prescribe any religious exercise. . . . must rest with the States" (emphasis added). Nevertheless, the federal courts ignore this succinct declaration and choose rather to misuse his separation phrase to strike down scores of State laws which encourage or facilitate public religious expressions. Such rulings against State laws are a direct violation of the words and intent of the very one from whom the courts claim to derive their policy.

One further note should be made about the now infamous "separation" dogma. The Congressional Records from June 7 to September 25, 1789, record the months of discussions and debates of the ninety Founding Fathers who framed the First Amendment. Significantly, not only was Thomas Jefferson not one of those ninety who framed the First Amendment, but also, during those debates not one of those ninety Framers ever mentioned the phrase "separation of church and state." It seems logical that if this had been the intent for the First Amendment – as is so frequently asserted-then at least one of those ninety who framed the Amendment would have mentioned that phrase; none did.

In summary, the "separation" phrase so frequently invoked today was rarely mentioned by any of the Founders; and even Jefferson's explanation of his phrase is diametrically opposed to the manner in which courts apply it today. "Separation of church and state" currently means almost exactly the opposite of what it originally meant.

Endnotes

1. Letter of October 7, 1801, from Danbury (CT) Baptist Association to Thomas Jefferson, from the Thomas Jefferson Papers Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. (Return)

2. Id. (Return)

3. The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia, John P. Foley, editor (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1900), p. 977; see also Documents of American History, Henry S. Cummager, editor (NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1948), p. 179. (Return)

4. Annals of the Congress of the United States (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1852, Eighth Congress, Second Session, p. 78, March 4, 1805; see also James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897 (Published by Authority of Congress, 1899), Vol. I, p. 379, March 4, 1805. (Return)

5. Thomas Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. I, p. 379, March 4, 1805. (Return)

6. Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies, From the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, editor (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1830), Vol. IV, pp. 103-104, to the Rev. Samuel Millar on January 23, 1808. (Return)

7. Jefferson, Writings, Vol. VIII, p. 112-113, to Noah Webster on December 4, 1790. (Return)

8. Jefferson, Writings, Vol. III, p. 441, to Benjamin Rush on September 23, 1800. (Return)

9. Jefferson, Writings, Vol. XVI, pp. 281-282, to the Danbury Baptist Association on January 1, 1802. (Return)

10. Richard Hooker, The Works of Richard Hooker (Oxford: University Press, 1845), Vol. I, p. 207. (Return)

11. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1794), Query XVIII, p. 237. (Return)

12. Reynolds v. U. S., 98 U. S. 145, 164 (1878). (Return)

13. Reynolds at 163. (Return)

Early Court Decisions on the Separation of Church and State

Runkel v. Winemiller, 1799

"Religion is of general and public concern and on its support depend, in great measure, the peace and good order of government, the safety and happiness of the people. By our form of government, the Christian religion is the established religion; and all sects and denominations of Christians are placed upon the same equal footing and are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty."

The People v. Ruggles, 1811

"[W]e are a Christian people and the morality of the country is deeply engrafted upon Christianity and not upon the doctrines or worship of those imposters [other religions].... [We are a] people whose manners... and whose morals have been elevated and inspired... by means of the Christian religion.

Though the constitution has discarded religious establishments, it does not forbid judicial cognizance of those offenses against religion and morality which have no reference to any such establishment... This [constitutional] declaration, noble and magnanimous as it is, when duly understood, never meant to withdraw religion in general, and with it the best sanctions of moral and social obligation from all consideration and notice of the law..."

Updegraph v. The Commonwealth, 1824

"The assertion is once more made that Christianity never was received as part of the common law of this Christian land; and... if it was, it was virtually repealed by the Constitution of the United States...

We will first dispose of what is considered the grand objection -- the constitutionality of Christianity... Christianity, general Christianity, is and always has been a part of the common law... not Christianity founded on any particular religious tenets; not Christianity with an established church... but Christianity with liberty of conscience to all men.

Thus this wise legislature framed this great body of laws for a Christian country and a Christian people.... [T]hus it is irrefragably proved that the laws and institutions of this State are built on the foundation of reverence for Christianity.... In this the Constitution of the United States has made no alteration nor in the great body of the laws which was an incorporation of the common-law doctrine of Christianity."

City of Charlston v. Benjamin, 1846

"Christianity is part of the common law of the land, with liberty of conscience to all. It has always been so recognized.... If Christianity is a part of the common law, its disturbance is punishable as common law. The U.S. Constitution allows it as part of the common law.... The observance of Sunday is one of the usages of the common law recognized by our U.S. and State Governments.... Christianity is part and parcel of the common law.... Christianity has reference to the principles of right and wrong... it is the foundation of those morals and manners upon which our society is formed; it is their basis. Remove it and they would fall... it [morality] has grown upon the basis of Christianity."

"What constitutes the standard of good morals? Is it not Christianity? There certainly is none other.... The day of moral virtue in which we live would, in an instant, if that standard were abolished, lapse into the dark and murky night of Pagan immorality...."

"In the Courts over which we preside, we daily acknowledge Christianity as the most solemn part of our administration. A Christian witness, having no scruples about placing his hand upon the book, is sworn upon the holy Evangelists -- the books of the New Testament which testify of our Savior's birth, life, death, and resurrection; this is so common a matter that it is little thought of as an evidence of the part which Christianity has in the common law...."

Commonwealth v. Nesbit, 1859

"By our... laws against vice and immorality we do not mean to enforce religion; we admit that to be impossible. But we do mean to protect our customs, no matter that they may have originated in our [Christian] religion; for they are essential parts of our social life.... Law can never become entirely infidel; for it is essentially founded on the moral customs of men and the very generating principles of these is most often religion."

Lindenmuller v. The People, 1860

"It would be strange for a people Christian in doctrine and worship, many of whom or whose forefathers had sought these shores for the privilege of worshipping God in simplicity and purity of faith, and who regarded religion as the basis of their civil liberty and the foundation of their rights, should, in their zeal to secure to all the freedom of conscience which they valued so highly, solemnly repudiate and put beyond the pale of the law the religion which was dear to them as life and dethrone the God who they openly and avowedly professed to believe had been their protector and guide as a people."

"All agreed that the Christian religion was engrafted upon the law and entitled to protection as the basis of our morals and the strength of our government."

Davis v. Beason, 1889

"Bigamy and polygamy are crimes by the laws of all civilized and Christian countries. They are crimes by the laws of the United States.... To extend exemption from punishment for such crimes would be to shock the moral judgment of the community. To call their advocacy a tenet of religion is to offend the common sense of mankind....

Probably never before in the history of this country has it been seriously contended that the whole punitive power of the government for acts recognized by the general consent of the Christian world... must be suspended in order that the tenets of a religious sect... may be carried out without hindrance."

Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 1892

"No purpose of action against religion can be imputed to any legislation, state or national, because this is a religious people.... These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic [official, governmental] utterances that this is a Christian nation."

United States v. Macintosh, 1931

"We are a Christian people... according to one another the equal right of religious freedom and acknowledging with reverence the duty of obedience to the will of God."

Zorach v. Clausen, 1952

"The First Amendment, however, does not say that in every and all respects there shall be a separation of Church and State.... Otherwise the State and religion would be aliens to each other -- hostile, suspicious, and even unfriendly....

We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.... When the State encourages religious instruction or cooperates with religious authorities... it follows the best of our traditions. For it then respects the religious http://www.blogger.com/img/blank.gifnature of our people and accommodates the public service to their spiritual needs. To hold that it may not, would be to find in the Constitution a requirement that the government show a callous indifference to religious groups. That would be preferring those who believe in no religion over those who do believe.... [W]e find no constitutional requirement which makes it necessary for government to be hostile to religion and to throw its weight against efforts to widen the effective scope of religious influence.... We cannot read into the Bill of Rights such a philosophy of hostility to religion."

Court Rulings and Decisions prior to 1945

| • | Maryland Supreme Court, 1799: "Religion is of general and public concern, and on its support depend, in great measure, the peace and good order of government, the safety and happiness of the people. By our form of government, the Christian religion is the established religion; and all sects and denominations of Christians are placed upon the same equal footing, and are equally entitled to protection in their religious liberty." |

| • | In 1811 the New York state court upheld an indictment for blasphemous utterances against Christ, and in its ruling, given by Chief Justice Kent, the court said, "We are Christian people, and the morality of the country is deeply engrafted upon Christianity, and not upon the doctrines or worship of other religions. In people whose manners are refined, and whose morals have been elevated and inspired with a more enlarged benevolence, it is by means of the Christian religion."[43] |

| • | In 1861 this same court said that "Christianity may be conceded to be the established religion."[19] |

| • | Vidal v. Girad's Executors, 1844. "Why may not the Bible, and especially the New Testament, without note or comment, be read and taught as a divine revelation in [schools] — its general precepts expounded, its evidences explained and its glorious principles of morality inculcated? . . .Where can the purest principles of morality be learned so clearly or so perfectly as from the New Testament? — Unanimous Decision Commending and Encouraging the use of the Bible in Government-Run Schools.[43,48] |

| • | Commonwealth v. Nesbitt, 1859: The court listed representative actions into which, if perpetrated in the name of religion, the government had legitimate reason to intrude: human sacrifice concubinage, incest, injury to children, advocation and promotion of immorality, etc. In all other orthodox religious practices where the public prayer, the use of the scriptures or whatever, the government was not to interfere. The clearly understood of the intent of Jefferson's letter and the way his phrase was applied for nearly a century and a half.[48] |

| • | Reynolds v. United States, 1878: The Court presented Jefferson's full letter, not just the eight words, "A wall of Separation between Church and State" and summed the intent of his phrase "Congress was deprived of all legislative powers over mere [religious] opinions but was left free to reach [only those religious] actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order." [The rightful purpose of civil government regarding religion was] to interfere [with religion only] when [religious] principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order. In this is found the true distinction between what properly belongs to the church and what to the state."[48] |

| • | In the case of Holy Trinity v. United States in 1892, after thoroughly researching volumes of founder's documents and citing an amazing 89 precedents, declared: "These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation."[13] |

| • | As justice Douglas wrote for the majority of the Supreme Court in the United States v. Ballard case in 1944: The First Amendment has a dual aspect. It not only "forestalls compulsion by law of the acceptance of any creed or the practice of any form of worship" but also "safeguards the free exercise of the chosen form of religion."[20] |

Religion and Government — Equal Partners

After signing the American Declaration of Independence, the new Congress appointed a committee to design a great seal of the United States. Committeeman Thomas Jefferson suggested the seal should include the children of Israel in the wilderness, led day and night by cloud and fire. Committeeman Ben Franklin suggested a more fitting image would be Moses, dividing the red sea, and pharaoh in his chariot being swamped by the returning waters. And the motto: "Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God."[30]

The Continental Congress hired a chaplain — Rev. Jacob Duche, an Episcopal minister — to open their first meeting in 1774 with prayer. Rev. Duche read the Episcopal Church's assigned scripture reading for that day which just happened to be Psalm 35 that reads, in part, "Plead my cause, O LORD, with those who strive with me; Fight against those who fight against me. Take hold of shield and buckler, And stand up for my help. Also draw out the spear, And stop those who pursue me." (NKJV) Then Rev. Duche led them into a long and extemporaneous prayer. The Psalm and the prayer were very moving to the delegates. John Adams wrote his wife Abigail, "I never saw a greater effect upon [an] audience. It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to read on that morning. I must beg you to read that Psalm."[45]

Congress has been opening with prayer ever since.[45]

The Continental Congress appointed chaplains for itself and the armed forces, ... imposed Christian morality on the armed forces, and granted public lands to promote Christianity among the Indians. National days of thanksgiving and of "humiliation, fasting, and prayer" were proclaimed by Congress at least twice a year throughout the war.[16]

The Minutemen, so called because they could be called to fight a minute's notice had strong ties to Christianity. The Minutemen were largely deacons out of churches because it was people like the Rev Jonas Clark who rallied his church deacons to go out and defend their town from attack. One of the clear teachings they believed was that they had the God given right of self defense; that it was a Biblical right.[45]

Charles Carroll, signer of the Declaration and member of Continental Congress: "Without morals a republic cannot subsist any length of time; they therefore who are decrying the Christian religion, whose morality is so sublime and pure, which insures to the good eternal happiness, are undermining the solid foundation of morals, the best security for the duration of free governments." - The Life and Correspondence of James McHenry by Bernard C. Steiner 1907, from a letter from Charles Carroll, Nov. 4, 1800.[5]

"It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in the order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society. Before any man can be considered as a member of Civil Society, he must be considered as a subject of the Governour [sic] of the Universe." — James Madison[39]

"... prior to 1789 (the year that eleven of the thirteen states ratified the Constitution), many of the states still had constitutional requirements that a man must be a Christian in order to hold public office."[26]

"The reason that Christianity is the best friend of Government is because Christianity is the only religion that changes the heart." — President Thomas Jefferson[40]

From The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, Henry P. Johnston, ed. (New York: G.P. Putnams Sons, 1890), Vol. IV, P. 36: "Providence has given to our people the choice of their rulers. And it is the duty as well as the privilege and interest, of a Christian nation to select and prefer Christians for their rulers."[13]

"The Promulgation of the great doctrines of religion, the being, and attributes, and providences of one Almighty God; the responsibility to Him for all our actions, founded upon moral accountability; a future state of rewards and punishments; the cultivation of all the personal, social and benevolent virtues — these can never be a matter of indifference in any well-ordered community. It is, indeed,difficult to conceive how any civilized society can well exist without them." — Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story[37]

To the kindly influence of Christianity we owe that degree of civil freedom, and political and social happiness, which mankind now enjoys . . Whenever the pillars of Christianity shall be overthrown, our present republican forms of government - and all blessings which flow from them — must fall with them. — Jedediah Morse, Patriot, called "The Father of American Geography"[28]

James Wilson and William Patterson — placed on the Supreme Court by President George Washington, had prayer over juries in the U. S. Supreme Court room.[13]

We are a Christian people ... not because the law demands it, not to gain exclusive benefits or to avoid legal disabilities, but from choice and education and in a land thus universally Christian, what is to be expected, what desired, but that we shall pay due regard to Christianity? — Senate Judiciary Committee Report, January 19, 1853[5]

Government and the Bible

The Continental Congress, in 1777, recommended and approved that the Committee of Commerce "import 20,000 Bibles from Holland, Scotland, or elsewhere," because of the great need of the American people and the great shortage caused by the interruption of trade with England by the Revolutionary War.[14]

Under British law it had been illegal to print a Bible in the English Language in America; after Surrender of British at Yorktown 1781, Congress approved the plan and established a committee to oversee the printing of America's very first very own English Bible. The endorsement in the front of it read, "The United States and Congress assembled recommends this edition of the Bible to the inhabitants of the United States."[15]

The Church in the State

Church services were held The Old House of Representatives in what is now called Statuary Hall from 1807 to 1857. The first services in the Capitol, held when the government moved to Washington in the fall of 1800, were conducted in the "hall" of the House in the north wing of the building. In 1801 the House moved to temporary quarters in the south wing, called the "Oven," which it vacated in 1804, returning to the north wing for three years. ... The Speaker's podium was used as the preacher's pulpit.[16]

Manasseh Cutler, In his journal dated December 23, 1804, describes a four-hour communion service in the Treasury Building, conducted by a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend James Laurie: "Attended worship at the Treasury. Mr. Laurie alone. Sacrament. Full assembly. Three tables; service very solemn; nearly four hours."[16]

Within a year of his inauguration, Jefferson began attending church services in the House of Representatives. Madison followed Jefferson's example, although unlike Jefferson, who rode on horseback to church in the Capitol, Madison came in a coach and four. . . . Preachers of every Protestant denomination appeared. (Catholic priests began officiating in 1826.) As early as January 1806 a female evangelist, Dorothy Ripley, delivered a camp meeting-style exhortation in the House to Jefferson, Vice President Aaron Burr, and a "crowded audience." Throughout his administration Jefferson permitted church services in executive branch buildings. The Gospel was also preached in the Supreme Court chambers.[16]

John Quincy Adams, a US Senator in 1803, wrote in his diary, "Religious Service is usually performed on Sundays at the Treasury Office and at the Capitol. I went both forenoon and afternoon to the Treasury."[15]

Inside the Capitol, just off the rotunda, is a prayer and meditation room that was set aside by the 83rd Congress for members' use. The focal point of the room is a magnificent stained glass window depicting George Washington kneeling in prayer. Etched around him are the words from Psalm 16:1 "Preserve me, O God, for in thee do I put my trust."[17]

Religion in Public Education

In Benjamin Franklin's 1749 plan of education for public schools in Pennsylvania, he insisted that schools teach "the necessity of a public religion . . . and the excellency of the Christian religion above all others, ancient or modern."[13]

Thomas Paine, in his discourse on "The Study of God," forcefully asserts that it is "the error of schools" to teach sciences without "reference to the Being who is author of them: for all the principles of science are of Divine origin." He laments that "the evil that has resulted from the error of the schools in teaching [science without God] has been that of generating in the pupils a species of atheism."[13]

The following five quotations are from "A Defense of the Use of the Bible in Schools" (1830) by Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration, member of Continental Congress, and founder of 5 universities.

"Let the children ... be carefully instructed in the principles and obligations of the Christian religion. This is the most essential part of education.[36]

"In Scotland and in parts of New England, where the Bible has been long used as a schoolbook, the inhabitants are among the most enlightened in religions and science, the most strict in morals, and the most intelligent in human affairs of any people whose history has come to my knowledge upon the surface of the globe."[36]

"We err, not only in human affairs but in religion likewise, only because we do not "know the Scriptures" and obey their instructions. Immense truths, I believe, are concealed in them. The time, I have no doubt, will come when posterity will view and pity our ignorance of these truths as much as we do the ignorance sometimes manifested by the disciples of our Savior, who knew nothing of the meaning of those plain passages in the Old Testament which were daily fulfilling before their eyes.

"The perfect morality of the Gospel rests upon a doctrine which, though often controverted, has never been refuted; I mean the vicarious life and death of the Son of God … By withholding the knowledge of this doctrine from children, we deprive ourselves of the best means of awakening moral sensibility in their minds . . .I cannot but suspect that the present fashionable practice of rejecting the Bible from our schools has originated from deists. And they discovered great ingenuity in this new mode of attacking Christianity. If they proceed in it, they will do more in a half a century in extirpating our religion than Bolingbroke or Voltaire could have effected in a thousand years " — Benjamin Rush: A Defense of the Use of the Bible in Schools[36]

"Surely future generations wouldn't try to take the Bible out of schools. In contemplating the political institutions of the United States, if we were to remove the Bible from schools, I lament that we could be wasting so much time and money in punishing crime and would be taking so little pains to prevent them."[5]

Charles Carroll, signer of the Declaration and member of Continental Congress: "Without morals a republic cannot subsist any length of time; they therefore who are decrying the Christian religion, whose morality is so sublime and pure, which insures to the good eternal happiness, are undermining the solid foundation of morals, the best security for the duration of free governments." The Life and Correspondence of James McHenry by Bernard C. Steiner 1907, from a letter from Charles Carroll, Nov. 4, 1800.[5]

Thomas Jefferson signed a bill to build a church at government expense for the Indians. He signed a bill to pay the salary of a missionary to the Indians. He recommended and signed treaties which gave federal government money to support a Roman Catholic priest in his priestly duties and to help build a Roman Catholic church. Jefferson, while president, was also the Chairman of the Board for education in Washington, DC, and he required that two books be taught in our schools — the Bible and Watt's Hymnal. "Thomas Jefferson, the guru of separation of church and state, whose name has been lifted up as a reason for snatching away Bibles from numerous little kids who have read them on recess or at their lunch break because they say Thomas Jefferson would never countenance having Bibles in the school. He mandated it!!"[3, 20]

Noah Webster, Founding Father, scholar, author of the first and still respected American Dictionary: "The religion which has introduced civil liberty, is the religion of Christ and His apostles, which enjoins humility, piety and benevolence; which acknowledges in every person a brother, or a sister, and a citizen with equal rights. This is genuine Christianity, and to this we owe our free constitutions of governments." 1832, History of the United States, Noah Webster, America's God and Country, William Federer, p.678[5]

John Marshal argued, by some to be our greatest Chief Justice of the Supreme Court: "The American population is entirely Christian, and with us Christianity and religion are identified. It would be strange indeed, if such a people, our institutions did not presuppose Christianity, and did not often refer to it, and exhibit relations with it." - letter to Jasper Adams, May 9, 1833[5]

Public Religious Testimonies in our National Capital

The words "In God We Trust" are inscribed in the House and Senate chambers.[21]

On the walls of the Capitol dome, these words appear: "The New Testament according to the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ."[21]

The Capitol Rotunda contains eight massive oil paintings, each depicting a major event in history. Four of these paintings portray Jesus Christ and the Bible: 1) Columbus landing on the shores of the New World, and holding high the cross of Jesus Christ, 2) a group of Dutch pilgrims gathered around a large, opened Bible, 3) a cross being planted in the soil, commemorating the discovery of the Mississippi River by the Explorer DeSoto, and 4) the Christian baptism of the Indian convert Pocahontas.[14]

Also in the Rotunda is the figure of the crucified Christ.[21]

Statuary Hall contains life size statues of famous citizens that have been given by individual states. Medical missionary Marcus Whitman stands big as life, holding a Bible. Another statue is of missionary Junipero Serra, who founded the missions of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Monterey and San Diego. Illinois sent a statue of Francis Willard, an associate of the evangelist Dwight L. Moody.[14]

The Latin phrase Annuit Coeptis, "[God] has smiled on our undertaking," is inscribed on the Great Seal of the United States.[21]

Under the Seal is the phrase from Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: "This nation under God."[21]

President Eliot of Harvard chose Micah 6:8 for the walls of the Library of Congress: "He hath shown thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?" (KJV).[21]

Also inscribed on the walls of the Library of Congress honoring the study of art, is "Nature is the art of God." A quote honoring Science says, "The heavens declare the glory of God."[14]

The lawmakers' library quotes the psalmist's acknowledgment of the beauty and order of creation: "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament showeth His handiwork" Psalm 19:1 KJV).[21]

Engraved on the metal cap on the top of the Washington Monument are the words: "Praise be to God." Lining the walls of the stairwell are numerous Bible verses: "Search the Scriptures" (John 5:39 KJV), "Holiness to the Lord," and "Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it" (Proverbs 22:6 KJV).[21]

At the opposite end of the Lincoln Memorial, words and phrases from Lincoln's second inaugural address allude to "God," the "Bible," "providence," "the Almighty," and "divine attributes."[21]

A plaque in the Dirksen Office Building has the words "IN GOD WE TRUST" in bronze relief.[21]

The Ten Commandments hang over the Supreme Court bench.[21]

Original Intent Of First Amendment

The words "Separation of Church and State" are NOT FOUND in any American Founding Document.